Later years

Victorian farthing, 1885

On 17 March 1883, she fell down some stairs at Windsor, which left her lame until July; she never fully recovered and was plagued with rheumatism thereafter.[157] Brown died 10 days after her accident, and to the consternation of her private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, Victoria began work on a eulogistic biography of Brown.[158] Ponsonby and Randall Davidson, Dean of Windsor, who had both seen early drafts, advised Victoria against publication, on the grounds that it would stoke the rumours of a love affair.[159] The manuscript was destroyed.[160] In early 1884, Victoria did publish More Leaves from a Journal of a Life in the Highlands, a sequel to her earlier book, which she dedicated to her "devoted personal attendant and faithful friend John Brown".[161] On the day after the first anniversary of Brown's death, Victoria was informed by telegram that her youngest son, Leopold, had died in Cannes. He was "the dearest of my dear sons", she lamented.[162] The following month, Victoria's youngest child, Beatrice, met and fell in love with Prince Henry of Battenberg at the wedding of Victoria's granddaughter Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine to Henry's brother Prince Louis of Battenberg. Beatrice and Henry planned to marry, but Victoria opposed the match at first, wishing to keep Beatrice at home to act as her companion. After a year, she was won around to the marriage by Henry and Beatrice's promise to remain living with and attending her.[163]

Victoria was pleased when Gladstone resigned in 1885 after his budget was defeated.[164] She thought his government was "the worst I have ever had", and blamed him for the death of General Gordon at Khartoum.[165] Gladstone was replaced by Lord Salisbury. Salisbury's government only lasted a few months, however, and Victoria was forced to recall Gladstone, whom she referred to as a "half crazy & really in many ways ridiculous old man".[166] Gladstone attempted to pass a bill granting Ireland home rule, but to Victoria's glee it was defeated.[167] In the ensuing election, Gladstone's party lost to Salisbury's and the government switched hands again.

Golden Jubilee

In 1887, the British Empire celebrated Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Victoria marked the fiftieth anniversary of her accession on 20 June with a banquet to which 50 kings and princes were invited. The following day, she participated in a procession that, in the words of Mark Twain, "stretched to the limit of sight in both directions" and attended a thanksgiving service in Westminster Abbey.[168] By this time, Victoria was once again extremely popular.[169] Two days later on 23 June,[170] she engaged two Indian Muslims as waiters, one of whom was Abdul Karim. He was soon promoted to "Munshi": teaching her Hindi-Urdu, and acting as a clerk.[171] Her family and retainers were appalled, and accused Abdul Karim of spying for the Muslim Patriotic League, and biasing the Queen against the Hindus.[172] Equerry Frederick Ponsonby (the son of Sir Henry) discovered that the Munshi had lied about his parentage, and reported to Lord Elgin, Viceroy of India, "the Munshi occupies very much the same position as John Brown used to do."[173] Victoria dismissed their complaints as racial prejudice.[174] Abdul Karim remained in her service until he returned to India with a pension on her death.[175]Victoria's eldest daughter became Empress consort of Germany in 1888, but she was widowed within the year, and Victoria's grandchild Wilhelm became German Emperor as Wilhelm II. Under Wilhelm, Victoria and Albert's hopes of a liberal Germany were not fulfilled. He believed in autocracy. Victoria thought he had "little heart or Zartgefühl [tact] – and ... his conscience & intelligence have been completely wharped [sic]".[176]

Gladstone returned to power aged over 82 after the 1892 general election. Victoria objected when Gladstone proposed appointing the Radical MP Henry Labouchere to the Cabinet, and so Gladstone agreed not to appoint him.[177] In 1894, Gladstone retired and, without consulting the outgoing prime minister, Victoria appointed Lord Rosebery as prime minister.[178] His government was weak, and the following year Lord Salisbury replaced him. Salisbury remained prime minister for the remainder of Victoria's reign.[179]

Diamond Jubilee

Queen Victoria in her Diamond Jubilee photograph (London, 1897)

The prime ministers of all the self-governing dominions were invited, and the Queen's Diamond Jubilee procession through London included troops from all over the empire. The parade paused for an open-air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul's Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage. The celebration was marked by great outpourings of affection for the septuagenarian Queen.[182]

Victoria visited mainland Europe regularly for holidays. In 1889, during a stay in Biarritz, she became the first reigning monarch from Britain to set foot in Spain when she crossed the border for a brief visit.[183] By April 1900, the Boer War was so unpopular in mainland Europe that her annual trip to France seemed inadvisable. Instead, the Queen went to Ireland for the first time since 1861, in part to acknowledge the contribution of Irish regiments to the South African war.[184] In July, her second son Alfred ("Affie") died; "Oh, God! My poor darling Affie gone too", she wrote in her journal. "It is a horrible year, nothing but sadness & horrors of one kind & another."[185]

Death and succession

Following a custom she maintained throughout her widowhood, Victoria spent the Christmas of 1900 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Rheumatism in her legs had rendered her lame, and her eyesight was clouded by cataracts.[186] Through early January, she felt "weak and unwell",[187] and by mid-January she was "drowsy ... dazed, [and] confused".[188] She died on Tuesday 22 January 1901 at half past six in the evening, at the age of 81.[189] Her son, the future King Edward VII, and her eldest grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, were at her deathbed.[190]In 1897, Victoria had written instructions for her funeral, which was to be military as befitting a soldier's daughter and the head of the army,[94] and white instead of black.[191] On 25 January, Edward VII, the Kaiser and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, helped lift her into the coffin.[192] She was dressed in a white dress and her wedding veil.[193] An array of mementos commemorating her extended family, friends and servants were laid in the coffin with her, at her request, by her doctor and dressers. One of Albert's dressing gowns was placed by her side, with a plaster cast of his hand, while a lock of Brown's hair, along with a picture of him, were placed in her left hand concealed from the view of the family by a carefully positioned bunch of flowers.[94][194] Items of jewellery placed on Victoria included the wedding ring of John Brown's mother, given to her by Brown in 1883.[94] Her funeral was held on Saturday 2 February in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, and after two days of lying-in-state, she was interred beside Prince Albert in Frogmore Mausoleum at Windsor Great Park. As she was laid to rest at the mausoleum, it began to snow.[195]

Victoria reigned for a total of 63 years, seven months and two days making her the longest-reigning British monarch, and was the longest-lived until surpassed by Elizabeth II. She broke the previous record for the oldest living British monarch, set by her grandfather George III, by three days.[196] She was the last monarch of the House of Hanover in the United Kingdom. Her son and heir Edward VII belonged to her husband's House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Victoria was so long-lived that the next four monarchs after her—son Edward VII, grandson George V, and great-grandsons Edward VIII and George VI—were all born during her reign.

Legacy

See also: Cultural depictions of Queen Victoria

According to one of her biographers, Giles St Aubyn, Victoria wrote an average of 2500 words a day during her adult life.[200] From July 1832 until just before her death, she kept a detailed journal, which eventually encompassed 122 volumes.[201] After Victoria's death, her youngest daughter Princess Beatrice, was appointed her literary executor. Beatrice transcribed and edited the diaries covering Victoria's accession onwards, and burned the originals in the process.[202] Despite this destruction, much of the diaries still exist. In addition to Beatrice's edited copy, Lord Esher transcribed the volumes from 1832 to 1861 before Beatrice destroyed them.[203] Part of Victoria's extensive correspondence has been published in volumes edited by A. C. Benson, Hector Bolitho, George Earle Buckle, Lord Esher, Roger Fulford, and Richard Hough among others.[204]

Victoria was physically unprepossessing—she was stout, dowdy and no more than five feet tall—but she succeeded in projecting a grand image.[205] She experienced unpopularity during the first years of her widowhood, but was well liked during the 1880s and 1890s, when she embodied the empire as a benevolent matriarchal figure.[206] Only after the release of her diary and letters did the extent of her political influence become known to the wider public.[94][207] Biographies of Victoria written before much of the primary material became available, such as Lytton Strachey's Queen Victoria of 1921, are now considered out of date.[208] The biographies written by Elizabeth Longford and Cecil Woodham-Smith, in 1964 and 1972 respectively, are still widely admired.[209] They, and others, conclude that as a person Victoria was emotional, obstinate, honest, and straight-talking.[210]

The Victoria Memorial in front of Buckingham Palace was erected as part of the remodelling of the façade of the Palace a decade after her death.

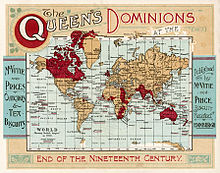

Map of the British Empire under Queen Victoria at the end of the nineteenth century

One of Victoria's children, her youngest son, Leopold, was affected by the blood-clotting disease haemophilia B and two of her five daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were carriers. Royal haemophiliacs descended from Victoria included her great-grandsons, Tsarevich Alexei of Russia, Alfonso, Prince of Asturias, and Infante Gonzalo of Spain.[215] The presence of the disease in Victoria's descendants, but not in her ancestors, led to modern speculation that her true father was not the Duke of Kent but a haemophiliac.[216] There is no documentary evidence of a haemophiliac in connection with Victoria's mother, and as male carriers always suffer the disease, even if such a man had existed he would have been seriously ill.[217] It is more likely that the mutation arose spontaneously because Victoria's father was old at the time of her conception and haemophilia arises more frequently in the children of older fathers.[218] Spontaneous mutations account for about 30% of cases.[219]

Around the world, places and memorials are dedicated to her, especially in the Commonwealth nations. Places named after her, include the capital of the Seychelles, Africa's largest lake, Victoria Falls, the capitals of British Columbia (Victoria) and Saskatchewan (Regina), and two Australian states (Victoria and Queensland).

The Victoria Cross was introduced in 1856 to reward acts of valour during the Crimean War, and it remains the highest British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand award for bravery. Victoria Day is a Canadian statutory holiday and a local public holiday in parts of Scotland celebrated on the last Monday before or on 24 May (Queen Victoria's birthday).

Titles, styles, and arms

Titles and styles

- 24 May 1819 – 20 June 1837: Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent

- 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901: Her Majesty The Queen

- 1 May 1876 – 22 January 1901: Her Imperial Majesty The Queen-Empress

Arms

Main article: Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom

Before her accession, Victoria received no grant of arms. As she could not succeed to the throne of Hanover, her arms as Sovereign did not carry the Hanoverian symbols that were used by her predecessors. Her arms have been borne by all of her successors on the throne, including the present Queen.Outside Scotland, the shield of Victoria's coat of arms—also used on her Royal Standard—was: Quarterly: I and IV, Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England); II, Or, a lion rampant within a double tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland); III, Azure, a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland). Within Scotland, the first and fourth quarters are occupied by the Scottish lion, and the second by the English lions. The Lion and the Unicorn supporters also differ between Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom.[221]

|

No comments:

Post a Comment